Daily Offices of the Church

The Church's daily offices have deep roots. In the Temple at Jerusalem, morning and

evening sacrifices were offered, and there were services of psalms and prayers at 9

am and 3 pm. Devout lay people prayed at home morning and evening as well.

On the Sabbath, synagogue services consisted of prayers and the reading

and exposition of the Scriptures. By Christ's lifetime, synagogues celebrated a

liturgy of the word on at least some weekdays.

The Church's daily offices have deep roots. In the Temple at Jerusalem, morning and

evening sacrifices were offered, and there were services of psalms and prayers at 9

am and 3 pm. Devout lay people prayed at home morning and evening as well.

On the Sabbath, synagogue services consisted of prayers and the reading

and exposition of the Scriptures. By Christ's lifetime, synagogues celebrated a

liturgy of the word on at least some weekdays.

The earliest Christian worship services were Sunday Eucharists, involving the reading of scriptures, prayer, and the breaking of bread, but as early as the second century two forms of daily offices grew up independently in the same period. The 'congregational' or 'cathedral' form of office developed in different places as people met daily together during the week for morning and evening services which consisted of psalms, canticles, prayers, and, in some places, scripture reading and instruction.

Clergy and laity were expected to attend these services, and those who could not were

expected to study the Scriptures and to pray at home at these times. The Jewish practice

of private prayer at the third, sixth, and ninth hours (9 a.m., noon, and 3 p.m.) was

retained and linked to events of the Passion. These two public offices came to be known as

Lauds and Vespers.

Clergy and laity were expected to attend these services, and those who could not were

expected to study the Scriptures and to pray at home at these times. The Jewish practice

of private prayer at the third, sixth, and ninth hours (9 a.m., noon, and 3 p.m.) was

retained and linked to events of the Passion. These two public offices came to be known as

Lauds and Vespers.

Simultaneously, the monastic or ‘choir’ offices were developing in various

forms in different parts of the world. They consisted of Scripture readings and the

reading of the entire Book of Psalms - in some places daily, in others weekly or

fortnightly. Hymns and prayers concluded the offices.

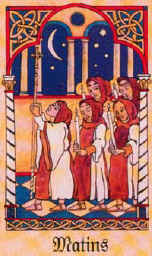

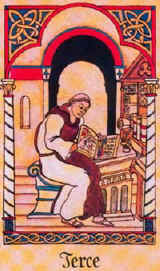

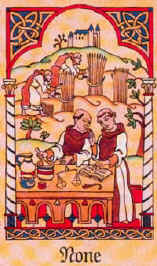

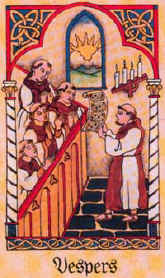

As the monks established communities in cities in the fourth century, the two forms of offices influenced one another. In time the number of daily offices grew to eight (Mattins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers and Compline). Both religious and secular Clergy were required to pray all of them, and lay people were invited to join the monks for two of the daily services, one in the morning, the other in the evening.

As this way of praying became formalized in institutions, lay people, most of whom did

not in any case read, became guests of the religious orders. But the services were in

Latin, which most lay people did not understand, and their availability depended on the

local presence of monastic institution which most parishes did not have. Moreover, as time

went on the services had become increasingly elaborate and complex.

As this way of praying became formalized in institutions, lay people, most of whom did

not in any case read, became guests of the religious orders. But the services were in

Latin, which most lay people did not understand, and their availability depended on the

local presence of monastic institution which most parishes did not have. Moreover, as time

went on the services had become increasingly elaborate and complex.

On March 7, 1549, a major moment in the reform and renewal of the Church of England,

the national Ecclesia Anglicana, had begun. The Book of the Common Prayer and

Administration of the Sacraments, and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, after the

use of the Church of England was ready for distribution at the office of the printer,

Edward Whitchurch, south of Fleet Street, in London. For the first time the services of

worship appointed for daily, Sunday, and occasional use were printed together in one book

and in "the vulgar tongue." Moreover, an act of Parliament required the

exclusive use of this Book of the Common Prayer and its services in all cathedrals and

parishes of the Church of England no later than Whitsunday, June 9, 1549.

On March 7, 1549, a major moment in the reform and renewal of the Church of England,

the national Ecclesia Anglicana, had begun. The Book of the Common Prayer and

Administration of the Sacraments, and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, after the

use of the Church of England was ready for distribution at the office of the printer,

Edward Whitchurch, south of Fleet Street, in London. For the first time the services of

worship appointed for daily, Sunday, and occasional use were printed together in one book

and in "the vulgar tongue." Moreover, an act of Parliament required the

exclusive use of this Book of the Common Prayer and its services in all cathedrals and

parishes of the Church of England no later than Whitsunday, June 9, 1549.

By mid-1549, therefore, all of England had the Bible and the Common Prayer in the

English language. No longer were daily prayer and Sunday worship to be in the Latin of

clerics and scholars, and thus inaccessible to the majority of the people of the realm.

By mid-1549, therefore, all of England had the Bible and the Common Prayer in the

English language. No longer were daily prayer and Sunday worship to be in the Latin of

clerics and scholars, and thus inaccessible to the majority of the people of the realm.

In Mattins and Evensong the eight medieval daily offices were compressed into two. What

had previously been seen as primarily the business of clergy, monks, and nuns was now

available in English and recommended for all. At their local church or in their homes, all

people could now be joined by the Holy Spirit to the communion of saints, together with

the angels and archangels, in offering daily worship to God on behalf of the

whole created order. United to Jesus Christ the Head of the Body, they could pray the

Psalter morning and evening as the intelligent members of the Body of Christ. And on

Wednesdays and Fridays, as well as on Sundays, they could intercede for one another by

joining in the Litany.

In Mattins and Evensong the eight medieval daily offices were compressed into two. What

had previously been seen as primarily the business of clergy, monks, and nuns was now

available in English and recommended for all. At their local church or in their homes, all

people could now be joined by the Holy Spirit to the communion of saints, together with

the angels and archangels, in offering daily worship to God on behalf of the

whole created order. United to Jesus Christ the Head of the Body, they could pray the

Psalter morning and evening as the intelligent members of the Body of Christ. And on

Wednesdays and Fridays, as well as on Sundays, they could intercede for one another by

joining in the Litany.

Following the publication of the first Book of the Common Prayer in 1549, there was a further modified edition in the reign of Edward VI, that of 1552. Between 1553 and 1558, the use of the English Prayer Book was forbidden by the Parliament under the Roman Catholic Queen Mary. In 1559, Elizabeth I restored the use of The Book of Common Prayer, the edition of 1552 with a few amendments. This edition of 1559, slightly modified again in 1604 by James I, served as the basis for the edition of 1662, which is still the most widely used edition of the Common Prayer and remains the official prayer book of the Church of England. The 1962 version is used within the Anglican Church of Canada, along with the Book of Alternative Services.

Acknowledgements:

Text adapted from Prayer Book Society of

Canada, Prayer

Book Society of the Episcopal Church

Images from The

Anglican Breviary